Water, Gender, and Poverty in Cambodia’s Stung Chinit Watershed

InAsia

Insights and Analysis

Water, Gender, and Poverty in Cambodia’s Stung Chinit Watershed

December 4, 2019

Poverty is complex, multifaceted, and deeply rooted in global, national, and local socioeconomic and power structures. In Cambodia, 17.7 percent of the population lives below a threshold of USD 1.90 a day, but the lived experience of poverty goes beyond monetary measures. The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) has developed a multidimensional poverty analysis framework (MDPA) that includes not only lack of material resources, but also lack of power and voice, human security, and opportunities and choice. The intent is to provide a more holistic definition of poverty, who is living in poverty, what keeps people in poverty, and why.

Four dimensions of poverty (adapted from Sida’s MDPA)

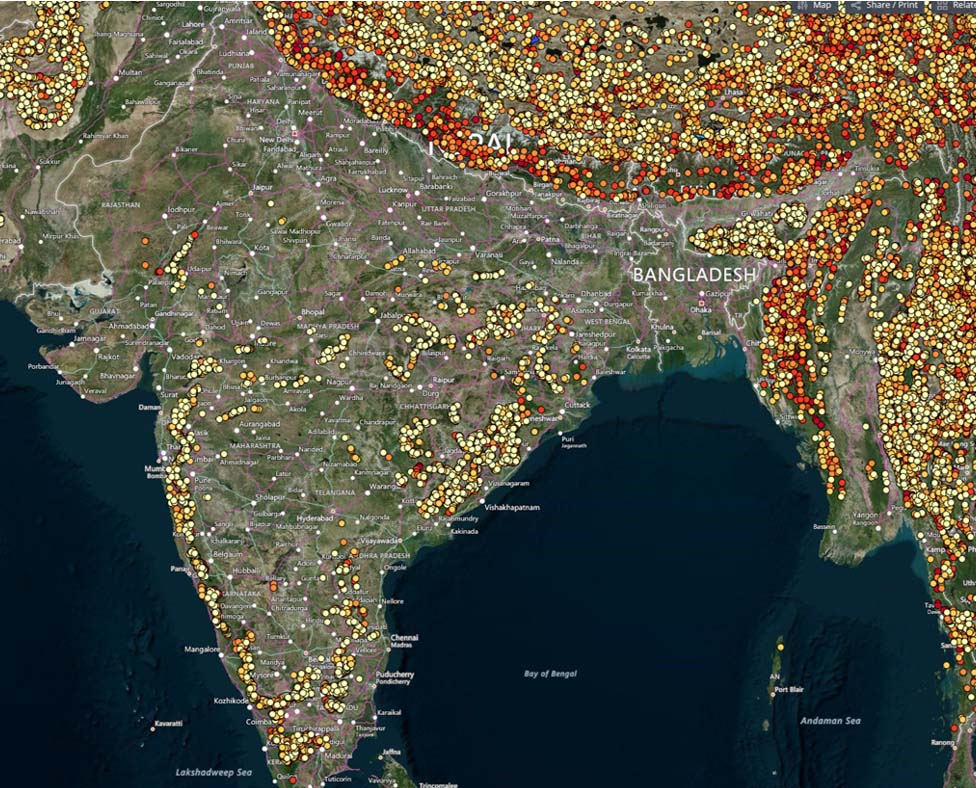

The Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), The Asia Foundation, and Winrock International are applying this framework to better understand the interconnectedness of water, gender, and poverty in the Stung Chinit Watershed in northeastern Cambodia. Here, we present preliminary findings of this analysis. Along with an extensive literature review, we conducted 14 key informant interviews with representatives of national, provincial, and local organizations and agencies, including the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, and the Stung Chinit Cheung Farmer Water User Committee. Our initial findings were used to develop a survey of 800 households, the results of which are currently being analyzed. This work builds upon previous watershed modeling and stakeholder engagement under the Sustainable Water Partnership funded by USAID, and findings will be integrated into the MDPA model and technical analysis in an effort to improve watershed management for gender equality and poverty reduction in the Stung Chinit basin.

How are water, gender, and poverty interlinked?

The Stung Chinit Watershed

The Stung Chinit River is a major tributary to Cambodia’s Tonlé Sap Lake, one of the world’s most productive ecosystems—half of Cambodia’s population benefits directly or indirectly from the resources that the lake provides—but also among Cambodia’s poorest regions, monetarily speaking. As in the rest of Cambodia, where agriculture, fishing, and forestry employ 70 percent of the labor force, the half million residents of the Stung Chinit basin rely heavily on the river for their livelihoods.

In the Stung Chinit Watershed, where clean drinking water can be scarce or unavailable and rice and fish provide the majority of food and income, access to water determines health, well-being, and livelihoods. Inequalities related to gender and poverty often affect access to water, and water access reinforces existing inequalities. Our initial research demonstrates this in three water-related dimensions: in the home, in agriculture, and in fishing.

Water for the home

Access to clean, potable water is a problem in rural areas, and it is income dependent, as the poor cannot afford to buy water filters or water purification tablets. According to representatives of the Ministry of Women’s Affairs and the Ministry of Rural Development, obtaining water for domestic use in Cambodia is primarily women’s responsibility, while men manage water for farming and economic activities. In rural areas where access to clean water is limited, women and girls in poor families may spend hours fetching water. In families that cannot afford storage tanks, women must collect water many times a day. When disasters strike, households rely on women’s knowledge to find water and properly treat it.

Because women are specifically responsible for water in the home, the Ministry of Rural Development is training women to repair wells and promote local sanitation. While these measures are important, they largely support women in serving the home and do not increase women’s economic independence or capacity.

A well in the backyard of a house in Kampong Thom Province (Photo: Koeung Socheat)

Water for agriculture

Farming practices are shaped by Cambodia’s climate, which includes high temperatures, a rainy season, and a dry season. Cambodian rice yields are low compared to other rice producing countries, mainly due to poor water management that results in either too much or too little water. For farming households that rely on rice crops for subsistence, low yields can lead to food shortages for two to five months of the year and a lack of surplus rice to sell for income.

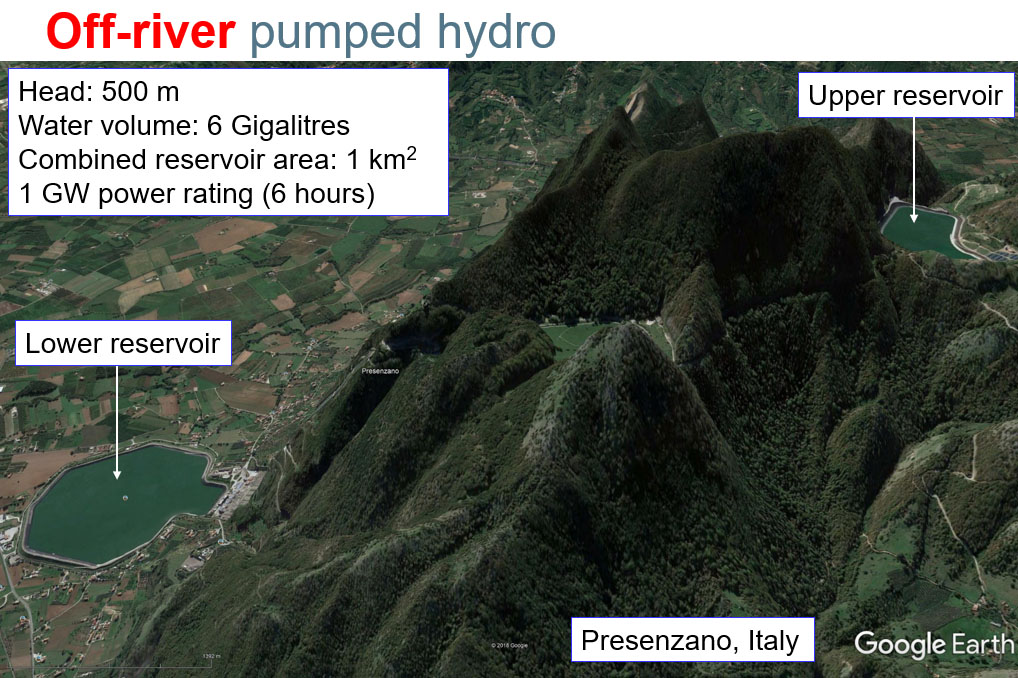

The Royal Government of Cambodia has invested in the construction of many large-scale irrigation schemes in the upper Tonlé Sap basin, including the Stung Chinit watershed, where two large reservoirs are used for irrigation and multiple smaller reservoirs and ponds supply water to farmers’ fields through a system of primary, secondary, and tertiary canals. The system is managed by the Provincial Department of Water Resources and Meteorology (PDOWRAM) and local Farmer Water User Communities (FWUCs). If located within the designated area, individuals can become FWUC members and receive water for irrigation.

In the Stung Chinit FWUC, livelihoods have improved for farmers with access to irrigation water, who can plant rice earlier, more reliably, and in the dry season. Representatives of the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology (MOWRAM) assert that this water is equally distributed regardless of age, ethnicity, or gender, and representatives of the Tonlé Sap Authority say that, apart from the lower-most part of the watershed, irrigation water is available year round. When key informants spoke about water for agriculture, most said reservoirs and canals are beneficial and provide equal access to water. Only a few recognized what is evident in the literature, that access to irrigation water depends on many factors—money and gender being two of them—particularly in the Stung Chinit watershed.

A house in the Stung Chinit watershed, in Kampong Thom Province (Photo: Chap Sreyphea)

Money. A representative of PDOWRAM stated clearly that if you have money, you get water. Belonging to an FWUC requires a fee. Getting water from canal to field requires electric pumping. If farmers can afford these things, they can get irrigation water. Those with more money, such as large-scale farmers, can afford to build their own ponds and irrigation systems.

Gender. According to representatives of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF), 64 percent of women in Cambodia are involved in agriculture. However, patriarchal gender norms create better opportunities for men in commercial or higher-income agricultural activities, while female household heads—who account for 20 percent of rural households—face significant challenges in obtaining irrigation water and agricultural land. MAFF officials speak of a machine revolution in Cambodian agriculture, where a large percentage of farmers now use electric tillers and other machinery. There is little data, however, on whether this revolution has reached women, who are typically considered incapable of handling such machinery or doing this kind of physical labor.

National government informants indicate that each government division or department should be at least 20–30 percent women, that women’s concerns are to be considered in ministry decision-making, and that there are efforts to strengthen women’s role in decision-making at the national level. Research shows, however, that this is not the case in the FWUCs, which directly control local access to water for agriculture. FWUCs, led largely by men, make the decisions about water allocation and operations. Men operate the gates that direct water to the fields. Women are often thought to lack the knowledge to participate in this decision-making or the ability to do this physical work, so women are excluded from FWUC discussions of irrigation planning. This puts female-headed households at a particular disadvantage in obtaining irrigation water for their crops.

Water for fishing

Cambodia previously granted water concessions to large-scale commercial fisheries via a system of fishing lots. Under this system, wealthy fishing lot owners had exclusive rights to harvest fish in a designated area, often in the most productive fishing grounds. Local communities and poorer subsistence fishers were denied access to those lots and had to comply with a fishing quota, which did not apply to lot owners. In recognition of the inequity of this system and the way it exacerbated the poverty of those with already limited resources, Cambodia abolished the lot system in 2015 in favor of community owned and managed fisheries.

The effects of this new system are still to be assessed. Early results suggest that wealthier groups and former fishing lot owners are overrepresented in community fisheries management and that poorer fisher groups are marginalized in these local decision-making bodies. Fisherwomen are further excluded, because they are not considered principal fishers. Time and further evaluation will tell whether this system reinforces existing inequities or creates equitable access to fishing for all.

The Stung Chinit River, a major tributary of Tonlé Sap Lake, one of the world’s most productive ecosystems (Photo: Chap Sreyphea)

Where do we go from here?

Our initial research suggests that there are critical problems of inequality surrounding access to domestic and irrigation water in the Stung Chinit basin. Exploring issues of gender and poverty allows us to ask who has power, a voice, and the opportunity to improve their situation, and how vulnerable are female-headed households, impoverished households, and those without access to safe drinking water.

The next step, our survey of 800 households, will explore in greater detail the dimensions of poverty and social relationships in the Stung Chinit watershed. The survey will also contribute to the development of a technical watershed planning model. A more comprehensive understanding of inequalities within the watershed will allow us to evaluate other links between water, gender, and poverty and to develop and test more robust solutions to eventually end poverty and inequality and to achieve truly equal access to water for all.

This post also appears, in slightly different form, in Perspectives, the blog of the Stockholm Environment Institute.

Susie Bresney is a staff scientist and Laura Forni is senior scientist at the Stockholm Environment Institute. Paula Uniacke is senior program officer for Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality at The Asia Foundation. They can be reached at [email protected], [email protected], and [email protected], respectively. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors, not those of The Asia Foundation.

About our blog, InAsia

InAsia is posted and distributed every other Wednesday evening, Pacific Time. If you have any questions, please send an email to [email protected].

Contact

For questions about InAsia, or for our cross-post and re-use policy, please send an email to [email protected].The Asia Foundation

465 California St., 9th Floor

San Francisco, CA 94104

The Latest Across Asia

Program Snapshot

April 18, 2024

News

April 17, 2024

2024 Lotus Leadership Awards

Thursday, April 25, 2024, New York City

The Lotus Leadership Awards recognize contributions towards gender equality in Asia and the Pacific